“I” Statements are a simple formula that promises peace, conflict-free homes, and to get what we want. Not so fast! Are they really that effective? Is that really the point? Do we even understand how to use them correctly? When do they work and when do they mess us up? Keep reading to find out the hidden pitfalls of “I” Statements.

We’ve all been taught to use an “I” Statement from self-help books or Communications 101. “I want you to be more kind to your sister.” And the child just complies like you’ve waved a magic wand over her head, right? Wrong.

“I need you to come home from work earlier to help with the kids every night.” I started with the word “I”, so why didn’t I get my wish fulfilled?

When there is no conflict, an “I” Statement is just fine to express what is needed: “I need you to help me unload the car.” The partner or child who is ready and willing will respond easily to this request. However, what about when there is a conflict? What about a non-compliant child or a spouse who sees things differently? How is an “I” statement intended to be used in these situations?

Take a look at these statements:

Statement 1 “I feel you are not listening to me when we discuss finances.”

What is the intent and motivation behind this statement?

Putting blame on the other, assuming we read their minds.

What reaction might it produce?

Response: “What do you mean? I am here right now and listening. You always blame me for everything going wrong with money? What about your reckless spending habits?”

Statement 2 “I want you to do your homework right now.”

What is the intent and motivation behind this statement?

Control and power

What reaction might it produce?

Response: “Well, I don’t want to. And you can’t make me!”

Statement 3 “I wish you weren’t so difficult and dismissive about fixing up the house.”

What is the intent and motivation behind this statement?

Negative labeling

What reaction might it produce?

Response: “I work all day, every day to keep a roof over our heads. You’re never appreciate anything I do.”

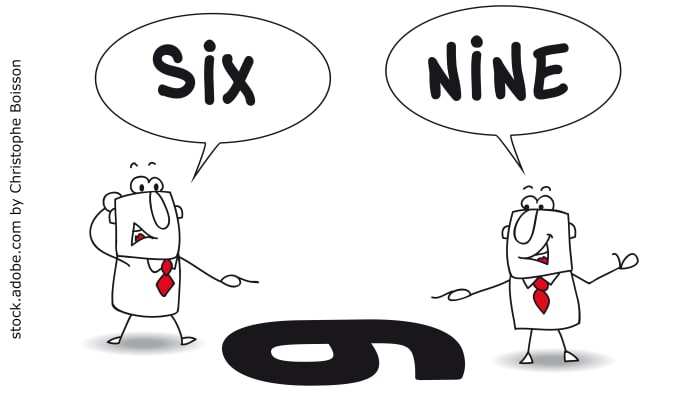

All these “I” statements are not self-reflective but putting oneself in a position of blame and control over the other. If there is a conflict, we cannot use “I” statements to wave our wishes over another person’s head and expect they will obey.

Likely, they will likely become defensive instead.

Just because we start a sentence with “I” doesn’t mean we can demand and expect compliance from the other person. The tension will escalate. Examine your motives before saying an “I” Statement during a disagreement. Is it to seek to understand or to get what you want? If it’s to get what you want, then no, don’t use it.

Rather than a tool, it becomes a weapon.

“I” statements, rather, are to express our needs, wants, and feeling about ourselves, not anyone else. They are offered with humility and sincerity to seek understanding when the other person has a difference of opinion.

The “You” statement that follows is for the Listener to restate what they heard. They would state what feelings, ideas, wants, the person said.

This approach is similar to the “Speaker-Listener Technique” taught in the book, “Fighting For Your Marriage.”

Speaker: “I feel so tired at the end of the week and want a special night out with you. I would like to take turns planning our date night.”

Listener: “What I heard you say is that you’re feeling tired at the end of every week and want to take turns planning a date night away from the kids.”

The “I” Statement person will confirm whether they were heard and understood correctly. If not, they state it again and the listener reflects what they heard. The important thing is to have no agenda for “winning” or getting your way. Just to be understood.

From Boston University we learn, “Ultimately, I-messages help create more opportunities for the resolution of conflict by creating more opportunities for constructive dialogue about the true sources of conflict.” Ideally, the “I” and “You” statements are to discover underlying issues: power, caring, recognition, commitment, integrity and acceptance. Once we can identify these needs in our statements, the real power of connection and understanding begins. Being understood sometimes is all we need, and we’ll be okay if the issue doesn’t resolve the way we had hoped.

Then the other person takes a turn and says their “I” statement that reflects how they feel about the issue, only stating their own needs. The “You” statement follows by the new Listener.

“I really don’t like planning dates. I am just not creative enough, but I do want to show you that I care.”

These two steps are crucial for seeking understanding in conflicted situations. There is no way to effectively solve a problem unless we seek to understand, without criticism, without agenda, without blame or power involved. Set aside your desire to fix or change the other person. The battle is not with them; rather, the two of you are a team to tackle a problem together.

The “I” Statement is followed by a “You” Statement and then a “We” Statement. The “We” compromise part may naturally happen after this back and forth, or the two people may need to think about it for awhile, to consider the other person’s point of view. Maybe later that night, or a few days or a week later, you will both have time to consider the validity of the other person’s view.

Compromise is not about 50/50: I get half my way if you get half your way. If that were the case, if one partner wanted Cherrywood cabinets and the other wanted Pine, they’d meet somewhere in the middle and get Oak…and both hate their kitchen cabinets. Rather, it is working as a team to find creative solutions and new perspectives to see a problem, and working together to get an answer.

No magic wand.

No fairy dust.

No easy answers, either.

Just plain and simple “I” and “You” talking and listening sincerely, without wanting to win.

References:

Markman, H. J., Stanley, S. M., & Blumberg, S. L. (2010). Fighting for your marriage: A deluxe

revised edition of the classic best seller for enhancing marriage and preventing divorce. San Fransico, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Office of the Boston University Ombuds Francine Montemurro, Boston University Ombuds,

chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.bumc.bu.edu/facdev-medicine/files/2011/08/I-messages-handout.pdf